Classification of Exoplanet Candidates

Exoplanets discoveries are the hot new science on the block. Chances are, you’ve heard something about exoplanets in the past few years. In case you haven’t, let me give you a quick overview.

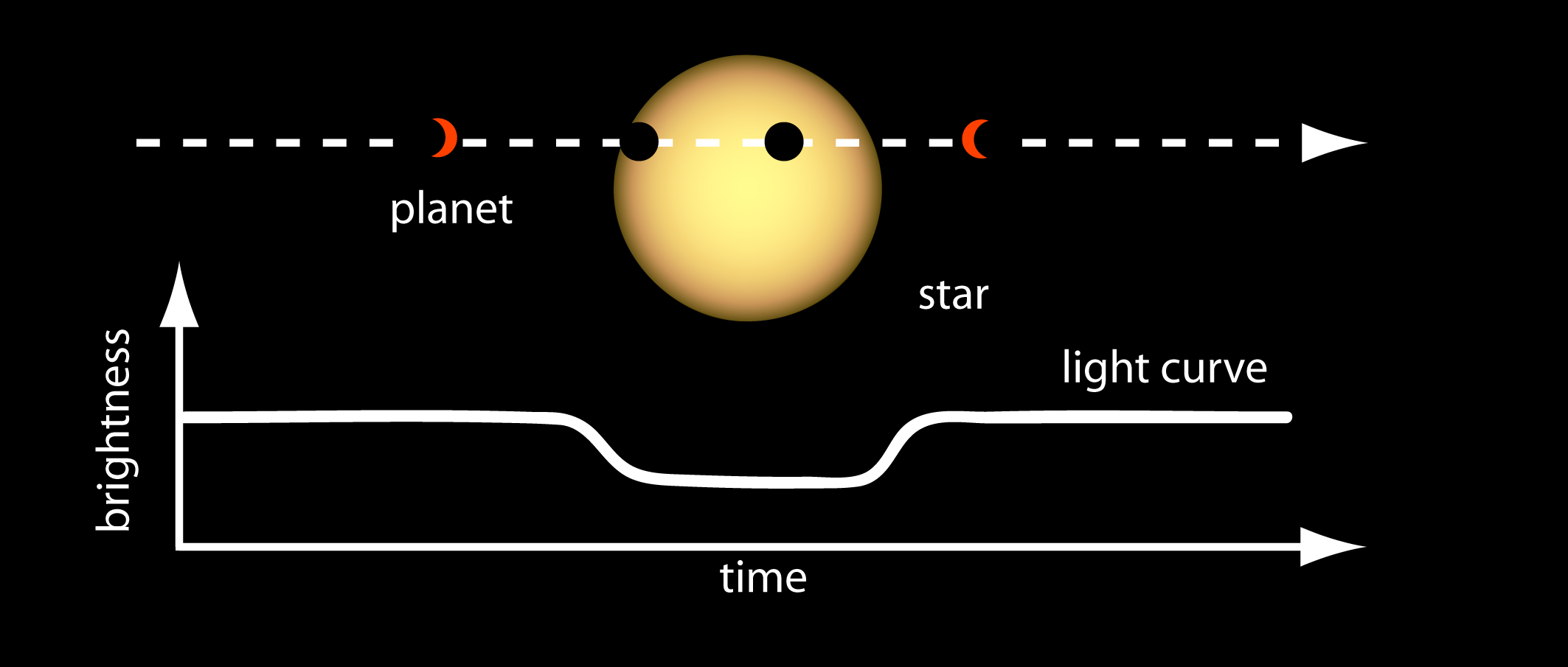

At the time of writing, 3,826 exoplanets have been discovered. Of those, 2,426 were discovered by a NASA mission called Kepler. Kepler uses something called the Transit Method to find exoplanet candidates, wherein an instrument samples the relative brightness of a star, and looks for any abrupt and unexplained drops in its brightness. If these drops in brightness exist in regular intervals, this is strong evidence of a planet orbiting that star. See the below graphic for an illustration of this effect.

|

|---|

| A simplified light curve obtained via the transit method |

Once NASA has a candidate on their hands, they begin the process of light curve analysis to classify this candidate as an exoplanet or not an exoplanet. I won’t get in to all the details of light curve analysis now, but suffice it to say that it is a time consuming and expensive process. My goal with this project was to investigate the possibility of an automatic classification system for exoplanets. Ideally, NASA would be able to use my model to filter candidates for those that are probable exoplanets, then use light curve analysis on those probable exoplanets, thereby significantly reducing the number of candidates they have to investigate.

Data

I got my data from the NASA Exoplanet Archive. It had 10,000 objects of interest in it to begin with, but 3000 of these objects had yet to be confirmed or disconfirmed yet (NASA is still analyzing these), so I removed those and ended up with about 6,900 candidates. 4,500 of these candidates were labeled as negative, and 2,400 were labeled as positive (eg confirmed) exoplanets.

I got straight to modeling, throwing every model I had ever heard of at this data. I decided early on that I wanted to use recall as my metric for model selection, because recall is directly analagous to the probability of detection, and I wanted my model to filter for true exoplanets as accurately as possible. Using 5-fold cross-validation, I was able to identify my immediate front runners as logistic regression, random forest, and gradient boosting.

Once I had my shortlist of models, I moved on to trying different sampling techniques and evaluating my models on test data that they had never seen. After trying several different combinations of upsampling and downsampling methods, I decided that minority upsampling via imblearn’s SMOTE function increased my models’ recall the most. Gradient boosting and random forest had identical recall, but random forest had a very slightly higher precision, so I ended up choosing random forest as my final model.

Results

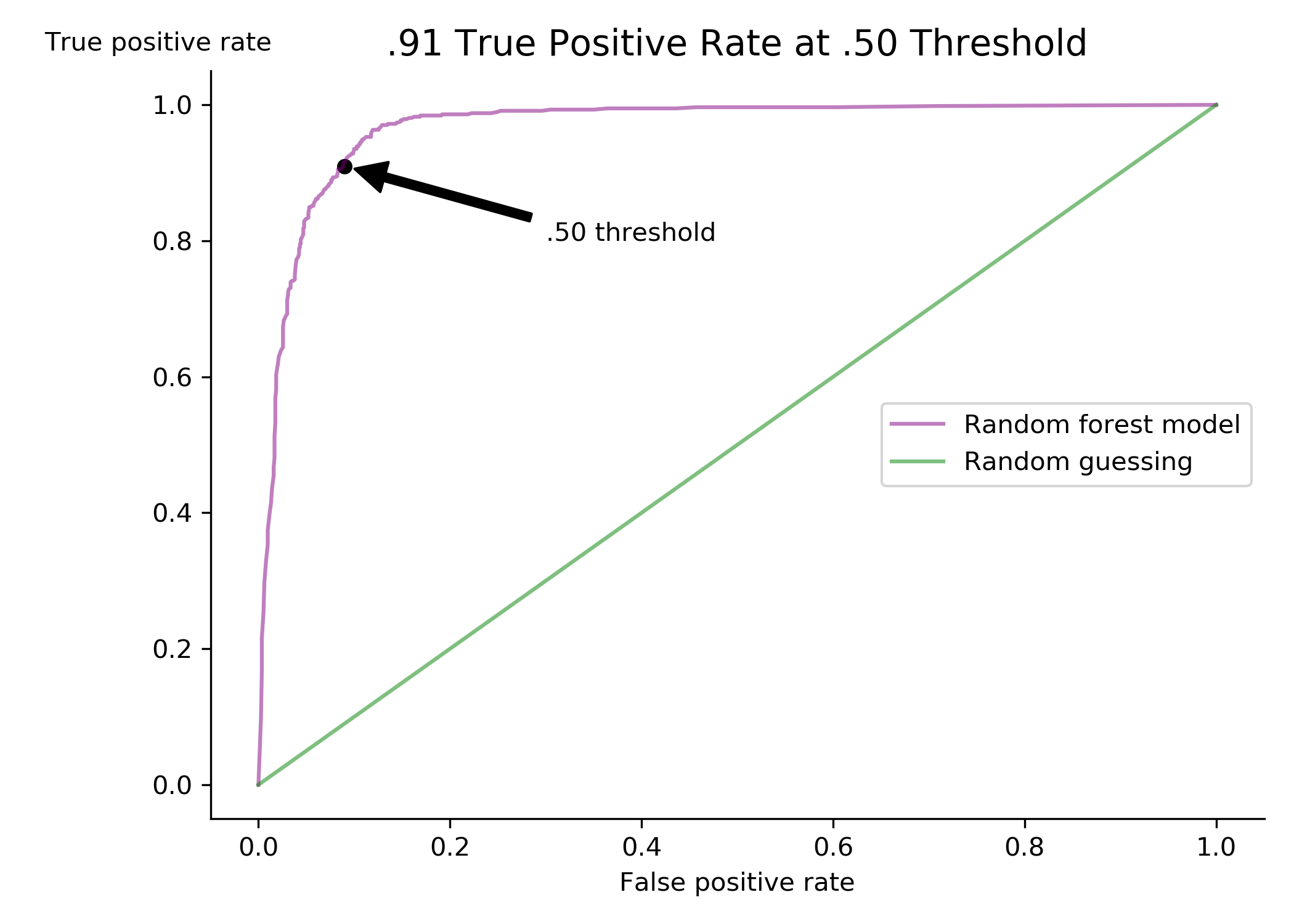

I’m very pleased with my model’s results. My model had recall of .91, precision of .92, and area under the receiving operator characteristic curve of .90. In cases with class imbalances like mine, people often tweak the probability threshold at which a model will predict a positive or negative classification. For example, I could have made my threshold .60 instead of .50, then my model need to estimate a 60% or higher probability of a candidate being an exoplanet for it to actually classify it as positive. However, this threshold is usually chosen through cost-benefit analyis. I found it difficult to put a meaningful cost on false-negatives and false-positive misclassifications, and decided to leave this part out of my analysis. If I revisit this project in the future, this is certainly an area I would improve.

|

|---|

| My model’s receiver operator characteristic curve |

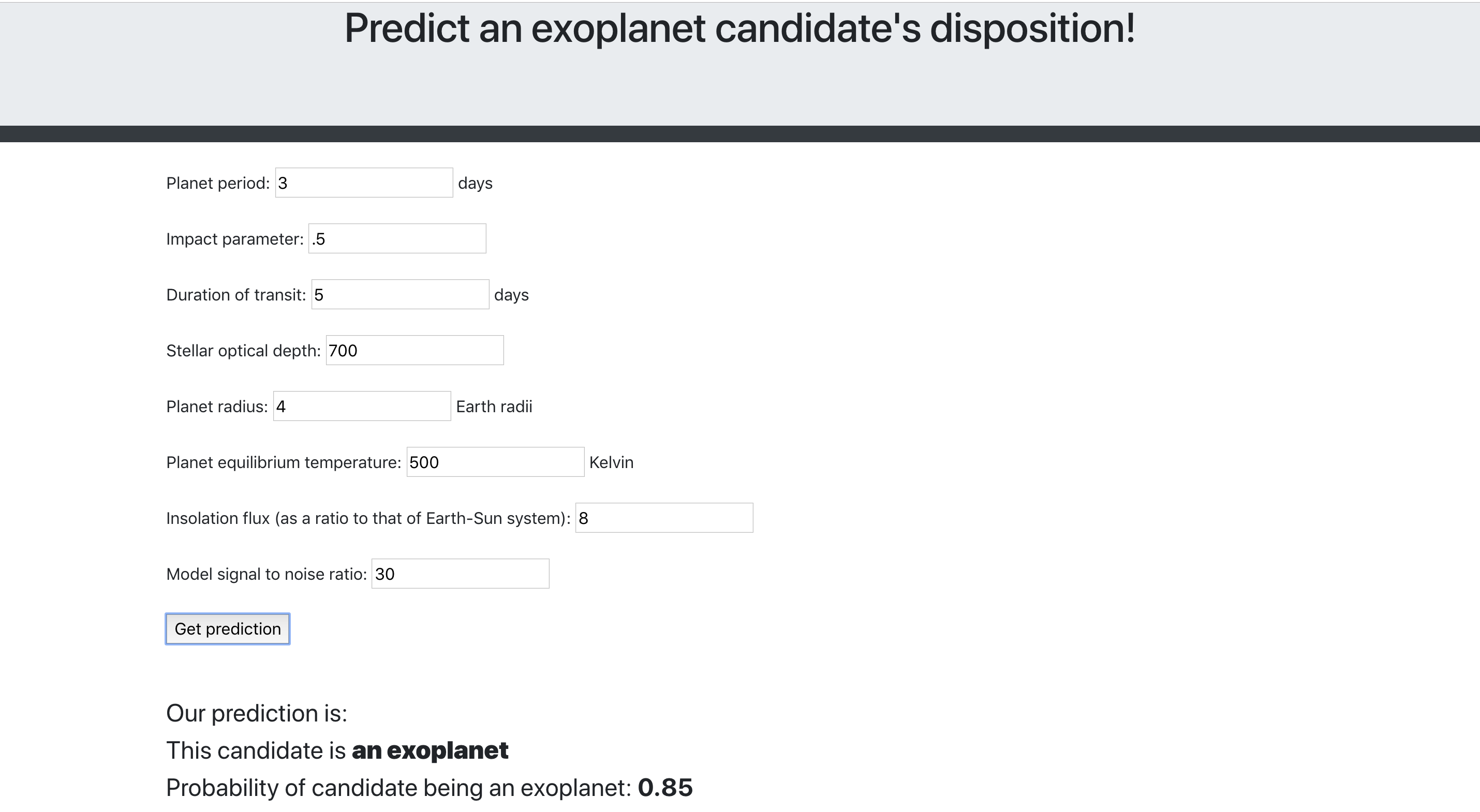

My model in its current state is quite good though. It’s not quite as good as this Cornell team’s neural network, but it’s getting there. I made a small Flask app that an astronomer could put exoplanet parameters in to and get a prediction and probability back out. A simple app like this could be used to do a quick pass of large sets of exoplanet candidates, grab the candidates that my model says are probable positives, and do light curve analysis on those candidates. If there’s extra money in the budget, then you can comb through the candidates my model identified as probable negatives.

|

|---|

| My humble Flask app |

Machine learning clearly has value in this very active problem space. The Kepler mission has entered the stage where NASA is having difficulty getting it to find more exoplanets, but rest assured there will be plenty more exoplanet candidates in the future. The James Webb Telescope is launching in 2021, and I expect it to find even more candidates than Kepler. As we step forward in this area of astronomy, it’s important that we do so with machine learning in mind.